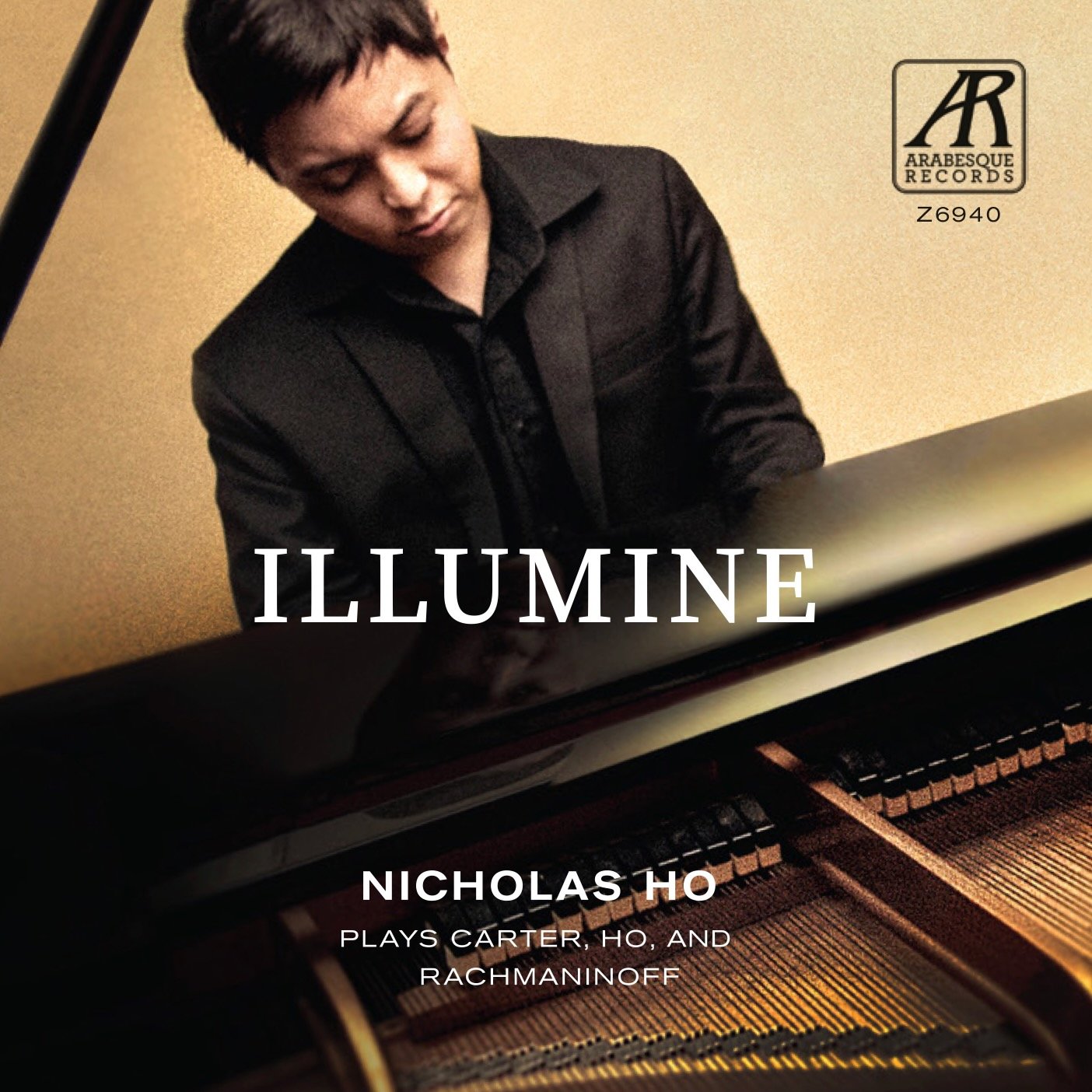

Illumine: an interview with pianist and composer Nicholas Ho

Very few pianists would consider pairing the music of Elliot Carter and Sergei Rachmaninoff on their first commercial recording. Even fewer would choose to round out the record with a suite of their own compositions. Pianist-composer Nicholas Ho has done just that, and it’s a testament to the quality of both his playing and his compositional skill that he did so successfully.

A former child prodigy born and raised in Singapore, Ho’s playing is elegant, effortless, intelligent, and playful. He approaches the notes with an eye to structure, while never sacrificing a singing, melodic line. These qualities shine through the music of Carter and Rachmaninoff, and they are the building blocks of Ho’s own suite of pieces, Inner States of Mind. It is here, in these brief, expressive pieces, that Ho combines the mathematical structure of Carter with the lyricism of Rachmaninoff. With these elegant pieces, Ho connects Carter and Rachmaninoff in a way that makes musical and intellectual sense, and his own voice and the sophistication of his music guarantees that they are works which transcend their setting.

Ho joins a long and illustrious line of classical pianist-composers—musicians who were once the norm but in this era of specialization are extremely rare. It’s to his credit that he does so at such a high level as both a composer and an interpreter of others’ music. I’m honored to feature him on No Dead Guys.

I understand that you were a child prodigy in Singapore and were featured on Channel NewsAsia's mini-documentary series, "Wonder Kids of Asia.” How has the prodigy label affected how people see you, and what do you wish people understood about musical prodigies?

There has always been an abundance of precocious talents across many fields – though realistically, not all prodigies go pro, pun intended! Many so-called prodigies are also expected to do great things, and they often burn out and fade away due to various reasons. Rising out of that label has not been easy. However, I’ve had the privilege of wonderful mentors throughout my journey who have kept me grounded, and with much humility in constantly trying to get better all the time, I am still going!

Perhaps growing up as a “prodigy” meant that I had to grow up faster, and I wish people understood that as a child, I wanted to experience the full gamut of being a child…

You’ve stated that in addition to piano lessons, you also studied the violin and that you credit your former violin instructor, Lim Soon Lee with being one of your biggest musical influences. How do you think that his teaching and musicality have made you a better pianist?

I’ve always loved the violin and will continue loving it for the rest of my life—in fact,I find myself still listening to more violin and orchestral music than piano music!

I think the biggest takeaway from my violin lessons lies in my awareness and sense of melodic lines, in terms of contour, phrasing, and intensity. The piano, being a more mechanical instrument, can sound exactly that way. Mr. Lim was also an extremely expressive musician, and I learned very much from his playing, which wowed me as a child. Of course, I began to incorporate that into my piano playing, especially in performance!

How old were you when you left Singapore to study in the United States and what was the most challenging thing about creating a life in a new country?

I served as a conscript in the Republic of Singapore Air Force right after high school and left for the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University, at age 21. The biggest challenge for me was missing my family. Being alone and starting a brand-new life was daunting, but I was fortunate to meet fellow Singaporeans in Bloomington during my freshman year. I also made wonderful friends from my studio, as well as from Chi Alpha Campus Ministries, which aided my transition into American life.

You write that Elliott Carter’s Piano Sonata encouraged you to start composing. Why do you think that this music, in particular, sparked your interest in writing your own music?

Perhaps one of the most interesting things about my background before my collegiate career was that I attended the National University of Singapore High School of Mathematics and Science. I remain the only graduate of my high school to pursue performing arts degrees, I believe! My mathematical and scientific training in high school has also led me to be more aware of things like structure and logic in music.

Elliott Carter’s Piano Sonata was perhaps one of the first pieces that paved the way for the New Complexity movement. It was my teacher then, Professor Edward Auer, who challenged me to learn the piece during the summer of 2017. It remains the most difficult piece I ever learned in terms of musical complexity.

There were two reasons why I started composing seriously. Firstly, I was initially disappointed that the Carter Piano Sonata ends so softly, especially after some amazing pianistic fireworks in the fugue, and I wanted to write a virtuosic showpiece that could follow it were I to program the work in recitals. I have since come to terms with that, understanding how the Carter Piano Sonata must end the way it did, for both the sake of mathematical and logical balance in form, and for its emotional impact that mirrors the ending of the Liszt Piano Sonata (which also ends softly). I have my initial naivety to thank! Secondly, it was probably a subconscious response for me to try to unravel the complexity in the Sonata, and to learn its secrets. The result was the Mirror Image étude that is featured in this recording. This étude is mathematical in nature, with both hands playing the same part, mirrored off the axis of Middle D—which also serves as a tribute to my time in NUS High.

How do you feel that your burgeoning career as a composer affects the way you understand and interpret the music of other composers?

As a composer, I realized that I was obsessively particular about the tiniest details in my music, even to the point of having my music engraved beautifully in Finale. I zealously revise my drafts, which include finding new solutions to passages that do not work and finding different chord voicings to test how they vibrate on the piano.

With that, I began to look at regular repertoire differently—these composers who preceded me probably meant every single note, and nothing was very much left to chance (we can argue about serial music another time!). I thus felt that it was my responsibility to study and understand music under the microscope, to be a great servant of music.

I was intrigued by your choice of pairing your composition, Inner States of Mind with the music of Elliott Carter and Sergei Rachmaninoff. It marks Illumine as a bold and diverse recording. Can you tell me why you chose to combine these particular pieces? And what do you think forms a thread between all of them?

Elliott Carter’s Piano Sonata is not widely performed, undeservedly, and I felt that recording it would be a great statement for me, especially for my first commercial release. I had also studied Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Sonata for many years, and absolutely adore it. While both sonatas were written just over 40 years apart, they are wildly different, and I wanted to show that I was a convincing interpreter of both worlds.

As for the inclusion of my suite in Illumine, I wanted to establish myself as a modern-day composer-pianist. After all, my musical idol Sergei Rachmaninoff, recorded both regular repertoire and his own works! It was exhilarating to at least attempt to follow in his footsteps.

Your composition Inner States of Mind is stunning. I’m extremely fond of the wide range of styles you featured in these five pieces. Can you tell me more about what influenced you to create each one?

After the success of my Two Études in a series of performances in Chicago, I was encouraged by both mentors and peers to continue composing. I had no prior compositional training at that point of time, which led me to experiment writing in different styles to find my voice. While practically flying blind, I was fortunate to stumble into creating four short pieces and found them suitable as a set.

Inner States of Mind, in its first form, was thus completed in 2018, during my first year as a master’s student in Piano Performance at the Chicago College of Performing Arts. After obtaining my bachelors at IU, I decided not to stay in Bloomington, to find fresh opportunities in Chicago. With that, I left my comfort zone in Bloomington behind, starting afresh yet again. I thus found myself in dark places—in hindsight, I was able to process these emotions healthily through my newfound passion in composition.

These pieces therefore narrate a spiritual and emotional journey I was going through in those dark times. As a Christian, in “What If?” I questioned and wrestled with God: if what I was going through was necessary, and if certain events in my life panned out differently. I chose intervals that represented pain, highlighting minor ninths and minor seconds. “Rainbows” illustrates a dark façade that brewed in my mind then: the possible illusion of joy. In this piece, I tapped into my ethnic Chinese heritage, and recreated the sound of the guzheng by a series of glissandos in the left-hand, which accompanied a melody in the right-hand. I was interested in breaking all the rules I knew and allowed this work to devolve into a series of loud and desperate crashing chords. Ending with a devastating whimper, it is the shortest piece of the set.

I adapted my early étude Mirror Image as the middle movement in this final version of the suite, as I found that it added to the narrative of the set, representing the chaos in my mind.

The final two movements of the suite hold special significance, as they reflected my acceptance of what I was going through, and how I was to overcome. A modern reinterpretation of the hymn, Benediction was also influenced by the chorale section in the finale of Carter’s Piano Sonata, in its use of irregular meters and rhythms. A cry for divine intervention, its introduction contains a paraphrase of a haunting ancient hymnal, Veni, Veni, Emanuel. Vantage Point is set in the distant future, where I see how things work together in their mysterious ways.

Naming the set Inner States of Mind was probably another tribute to my early mathematical and scientific training—there are four fundamental states of matter: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma, and man-made ones such as Bose-Einstein condensates. With diverse pieces in this suite (which also happens to contain some cyclical elements), I thought that this title absolutely fit the states my mind was in during those trying times.

While I enjoyed all 5 pieces in Inner States of Mind, my favorites were Benediction and Vantage Point. Tell me about your choice to end Benediction in such an open-ended way. Also, do you feel that Vantage Point provides something of an answer to Benediction?

Firstly, I love how the ending chord in Benediction resonates on the piano. I have never really thought deeply into it until today (thank you, subconscious thoughts then!), but perhaps the open-ended ending signifies a state of acceptance and openness to what life has in store. It also leads into the final movement in a perfect way.

So yes, I do believe that Vantage Point provides an answer to Benediction, in the sense that I may not understand how things work for good, but I trust that I will at some point. My reference Bible verse to this movement is from Psalm 121—“I lift my eyes up to the mountains; where does my help come from?”

I recall ardently the first time I performed this suite in public, at a place up in the mountains of Vermont at the Manchester Music Festival. What serendipity! It was an amazing experience, and a fellow musician came up to me with tears in her eyes, telling me how Vantage Point touched her the most. Such moments continue to inspire me to create, and in the process, touch my audiences.

What composers, other than Carter and Rachmaninoff influenced your compositional choices in Inner States of Mind?

For the étude, the most obvious answer is Bartok—similar compositional procedures are found in his piano oeuvre. As a pianist, the standard diet of Bach, Beethoven, Liszt, and Chopin has also informed my pianistic writing. From a compositional standpoint, I treated this suite as an experimental lab in developing my voice in composition, so perhaps bits of Ravel, Bruckner, Scriabin, jazz, gospel pop(!), film music, and anything under the sun crept their way into this suite.

Until the 20th century, most pianists were also composers. Today, in this era of specialization, how do you hope to build a career that combines both of these paths?

The career of a composer-pianist is one that is tried and tested until the 20th century, of course, with this breed of musicians becoming a rarity by the second half of the 20th century. Nevertheless, it is so interesting to me that pianists such as Evgeny Kissin and Stephen Hough, known for the longest time for their pianistic prowess on the concert stages, have also published and performed music of their own as of late. While we all seek fresh nterpretations of standard repertoire, it really does give the modern-day audience a different sense of excitement when a pianist performs his or her own works in concert. The pianist no longer functions as an intermediary between the composer and the audience, but as a direct connection to the music.

With that, I hope to continue playing concerts, programming my own music along the way. Composing does make me feel alive, and to see them come into fruition in concert is one of my greatest joys in life. I personally do not separate my compositional endeavors with my pianistic ones, as I see them both as part of my being.

Will you have sheet music available for Inner States of Mind? If so, where might we purchase it?

I do intend to publish and am weighing my options at the moment!

What current and future projects are you most excited about?

I am most excited about an album that I am working on now, which will include my biggest and most ambitious compositional project: an opus of twelve études for the piano! Chopin, Liszt, Debussy, and others have published sets of twelve études, and I hope to follow in that esteemed tradition. This opus is actually part of my doctoral capstone project at the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, where I am currently pursuing my Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance. I can’t wait to share these with the world!

The art song is also one of my favorite genres to write in – I am fortunate to be commissioned to write a small set of Singaporean art songs, with Singaporean poetry! I await its premiere with much excitement.

What advice can you offer to young musicians who wish to create dual careers as performers and composers?

As a young musician growing up, I saw performing and composition as two distinct paths. It was only when I started dabbling in composition, did I see its benefits in my interpretation of music as a performer. I oftentimes wonder how different a musician I’d become if I discovered composition earlier!

With that, I believe that young, aspiring performers, should learn to compose for at least their instruments as well. Short pieces, such compositional exercises and model compositions, could be a starting point. Even if one’s compositions are absolutely terrible, one would learn something, nonetheless. I was a chorister in high school until my voice broke. I was also just an average violinist. Still, some of my best compositions are represented in my works for voice and violin, namely, some of my art songs, and my Sonata for Violin and Piano (which is my first large-scale work!). There are lessons to be learned.

Hailed as a “gifted young artist”, Singaporean pianist-composer Nicholas Ho is active as both a performer and a composer. Notable performances include a New York City debut at Steinway Hall, an American concerto debut with the Rachmaninoff Third Piano Concerto at the Harris Theater for Music and Dance in Chicago.

Holding a Bachelor of Music from Indiana University and a Master of Music from the Chicago College of Performing Arts, he is now pursuing a Doctor of Musical Arts at the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music. His principal teachers include pianists Ong Lip Tat, Tedd Joselson, Edward Auer, and Ran Dank. Amongst various accolades, Nicholas was awarded the Jury Special Prize at the 5th Asian Youth Music Competition Open Category in 2012, Second Prize at the 2018 Young Concert Artists International Audition, and First Prizes at both the CCPA and CCM Concerto Competitions.

Nicholas also enjoys solving puzzles; he developed the "Sandwich Method", a direct-solving method for higher order Rubik's cubes (4x4x4 and above).