Fractures: an interview with composer and pianist Peter Michaels

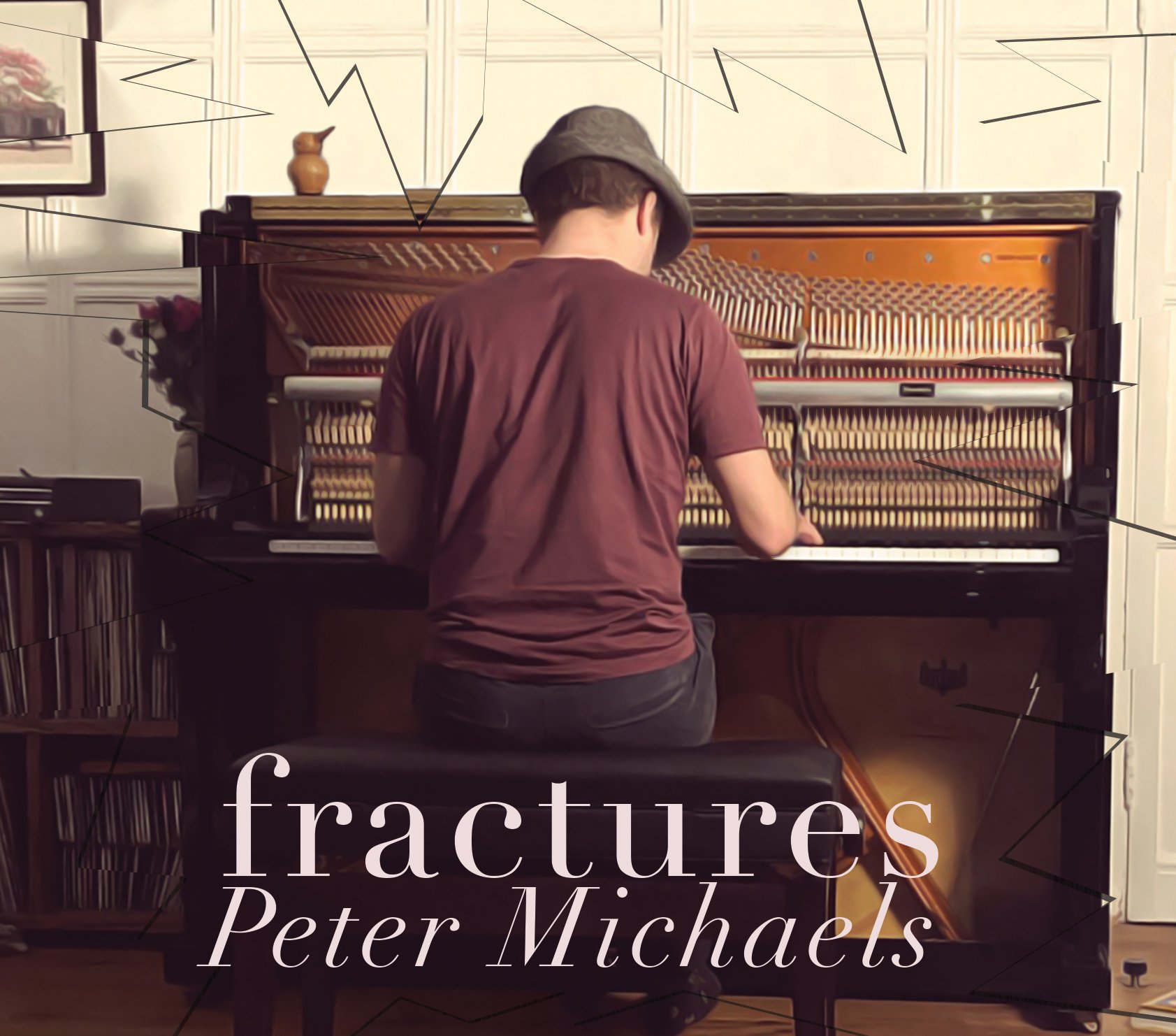

Composer and pianist Peter Michaels refuses to be defined by one style of music. In an era of hyper-specialization, he draws from classical and jazz training, Flamenco inspiration, and Brazilian rhythms. He was a founding member of the UK’s busiest Klezmer band, “The Matzoh Boys,” the Middle Eastern jazz band “Melange,” and the folk and blues band “Hunter Gatherers.” This diversity appears in his numerous compositions written for drama and film, and it is a defining feature in Fractures, Michaels’ recent release for solo piano.

Featuring Michaels as both composer and pianist, Fractures is a jewel box collection of diverse piano solos, each one showcasing the imaginative storytelling ability of the composer. The intimacy of the solo piano adds to each piece, bringing the cinematic scale down to hammers and felt and the warmth of human touch. It is an honor to feature Peter Michaels and Fractures on No Dead Guys.

What first attracted you to music and at what age did you start learning to play the piano?

My father was a musician, and he had a guitar case with ‘do not touch’ stuck on the side. That’s bound to attract the interest of any child!

We had a piano, which thankfully we were allowed and encouraged to play – it was a beautiful Bechstein from the 1890s and had so much character. Maybe I was 8 or 9 when I started, but I didn’t have lessons till a few years later.

When did you begin composing your own music and who or what inspired you to do so?

I probably started writing when I was about 12. The piano very much encourages composition – the notes are all laid out in front of you begging to be played! One of the first improvised piano albums I heard, in my teens, was Keith Jarrett’s Bremen & Lausanne concerts. I remember listening to those long improvisations with continuously developing themes and feeling like that was what I had been trying to do myself.

I understand that your undergraduate degrees were in mathematics and philosophy. Has your interest and training in both fields had any effect on how you make music? If so, how?

Yes, I think it has had an impact. Firstly, writing for film raises philosophical questions – what is the role of music in the story? How much should the audience be aware of the music and its impact on them? Asking questions like these often has a direct influence on what you choose to write.

Secondly, mathematical sequences can be used throughout music – cycles of fourths are an example – and can help you find new voices. One scale I remember coming across when I was 16 was the double-diminished scale – a repeating pattern for which I have found surprising uses for in the years since.

If you haven’t already, have a look at Gödel, Escher, Bach, by Douglas Hofstadter. He explores common threads between maths, philosophy and artistic creation, all in the form of a literary fugue.

Congratulations on your successful career as a performer, music producer, and a composer of music for drama, films, and songwriting. How did you break into writing film scores and what composers most influence your compositional style?

I started writing for plays with a friend of mine who was a theatre director. We took several shows to Edinburgh Fringe Festival, which was a great place for experimentation, and some of these included multi-media elements. I realized I loved writing music directly to footage, and that led to an interest in music for film.

In terms of influence, from a classical side it includes Bach with his inter-voice textures and Chopin’s use of lyrical melody – he always seems to be trying to get the piano to sing! I find the music of Brazil to contain so much inspiration, with Antonio Carlos Jobim’s compositions full of especially great examples of extended harmony and rhythm, all encased in the emotional pull of a song.

Given that your primary instrument is the guitar, what inspired you to compose your latest release, Fractures, for solo piano?

I find guitar to be a very collaborative instrument. I am often playing it in the context of a wider band, and much of its beauty lies in either supporting another instrument or playing individual lines over a rhythm section. I love to listen to solo guitar, but somehow haven’t found that to be my main direction with the instrument. When the pandemic hit, there was no opportunity for recording in groups (aside from a few Zoom recordings) so it felt like a natural time to work on a solo album – something I had never done before.

The piano has always been a relatively solo experience for me. I played the instrument in a few bands in my early twenties, but it is mainly a place of solace. I am happy improvising at the instrument for hours on end – so I wanted to capture some of that.

Fractures is a beautiful collection of pieces that cover a surprisingly wide range of styles. I understand that part of your journey in creating this music centered on the piano you chose for the project. What can you tell me about this?

I chose a wide range of music because I tend to move around as I play – from an initial Baroque ideal, into minimalism, then New Orleans inspired blues and so on. I wanted to find a piano that would travel with me down each path. This isn’t easy for an upright – I am limited in space – which often doesn’t have the depth of tone for slow, resonant chords, or the note separation needed for faster, dense playing. So when I went looking for pianos, I took with me an armory of pieces I had written that covered a huge range of styles, and these became the basis for the album.

Most of the tracks on Fractures felt very cinematic. How has your work as a drama and film composer influenced your ability to tell stories through music?

I often think visually when I am writing. I can see a series of images – sometimes just a feeling associated with those images, perhaps an emotion someone might be feeling during a scene – and the music becomes connected to that. For example “Fractured Waltz” was written for a film (that only exists in my mind at the moment) set in a forest in the distant past somewhere in middle Europe, at a time when magic lived amongst the trees.

In other cases, it isn’t visual so much as setting a striking part of a story to music. “Alma’s Lament” was written in response to my work on a play about Mahler and his wife Alma. She had been a composer in her youth, but gave that up once she became married, at Mahler’s request. I was trying to imagine a situation where I was not allowed to compose!

Another part of storytelling is naming the tunes. I find once a name comes into focus, so does the tune.

One of my favorite tracks on this album is “That Time Of The Night” which you wrote was influenced by modern jazz pioneers such as McCoy Tyner. In such a straight-up jazz tune, how much of the score was written out and how much was improvised?

Thank you, I’m pleased you like that one! Much of the tune was composed during improvisation, then by the time of recording I had a good deal of the structure set out. Each time I play it, I vary the chord voicings and some of the lines, as well as the short solo section in the middle. I love how McCoy found such big chords, creating huge drama on a single instrument, something only a piano can do.

“Lina’s Theme” is another favorite on mine—one that was based on the story of a young girl “who found school life difficult due to the severe challenges she faced at home.” Tell me a bit about your choice of balancing a haunting melody and open right hand notes against the heaviness of deep bass notes?

This piece was commissioned for an interactive game that took place in schools, to help children become more aware of the difficulties some of their peers are facing. A child’s behaviour is often caused by something that isn’t immediately obvious. I wanted to find a simple melody that showed an outward-facing childishness. Then underneath that is the huge weight of the burden Lina is facing at home – her mother is suffering severe mental illness. This feeling of needing to be the supportive grown-up is represented by the deep notes that rumble underneath the main melody.

Another favorite is “The Space Between The Stars” which I found to be a beautiful exploration of open-ended lyricism. What inspired this piece?

The piano! The instrument lets you play huge, open chords and leave them ringing out, whilst chiming melodies can dance over the top. That contrast gives me a feeling of vastness which ties into the sense of space. I often think our minds are too limited to really understand the immensity of what’s out there. I mean, what is a light-year, really? The idea that a distance can be measured by time is strange and wonderful to me.

Will you be offering sheet music for the tracks featured on this album? If so, where might we purchase it?

I have prepared sheet music for about half of it. I will probably make that available via my website later this year.

What current and future projects are you most excited about?

I am working on an album of new material with a fantastic harpist. I am arranging the music for synthesizer, as I have recently acquired a beautiful instrument – a Prophet 5 – inspired in part by the music of Ryuichi Sakamoto who often used that keyboard. For an instrument full of electrons, it feels alive – and pairs with the harp extremely well.

What advice can you offer young musicians seeking to create a career for themselves in music?

I think a lot of attention is focused on how to do what the most well-known musicians are doing currently – so in media composing, it is how to create the most epic, driving soundscape in the vein of the big blockbusters. That’s great to learn from, but it isn’t where you are going to start your career – you will be most noticed if you come up with something completely different, which grabs the interest of your peers, and hopefully that will get you the first jobs. Later, when Marvel calls, you can turn up the epic dial…

Peter Michaels is a composer, pianist and guitarist. His compositions have been featured on the BBC, and played on stages from the Royal Albert Hall and Wembley Stadium to the Washington Monument. With a background in classical music and jazz, he collaborates regularly with musicians from Brazil, India and the Middle East.

With violinist Felipe Karam, he formed Pocket Caravan to explore the links between the music of Brazil and Peter’s own Eastern European roots. Together with their quartet, they wrote three albums, and toured the UK, USA and Brazil. He was a founding member of several groups including the UK’s busiest Klezmer band, The Matzoh Boys, Middle Eastern jazz band Melange, with virtuoso cellist Shirley Smart, and folk and blues band Hunter Gatherers. His performance style blends his classical and jazz training with Flamenco inspiration and Brazilian rhythms.

He has composed for West End theatre and for BBC Drama, National Geographic, Sony, and Sky, as well as a creative partnership with Ninja Tunes for the feature film “The Habit of Beauty”. He has written scores for several documentaries including the recent ‘Six Inches of Soil’ which was the first farming documentary to be shown at the United Nations COP, and features Peter’s theme song ‘Living Roots’.