42 helpful hints for adult pianists: A guest article by author Howard Smith

A guest post by Howard Smith.

For piano teachers, there are few purer joys than working with a motivated adult pianist. Whether a beginner or “returner," adult learners enter piano lessons for the sheer joy of learning how to make music at the piano. There’s no parental pressure. They learn because they love music and that love shines through every note they play.

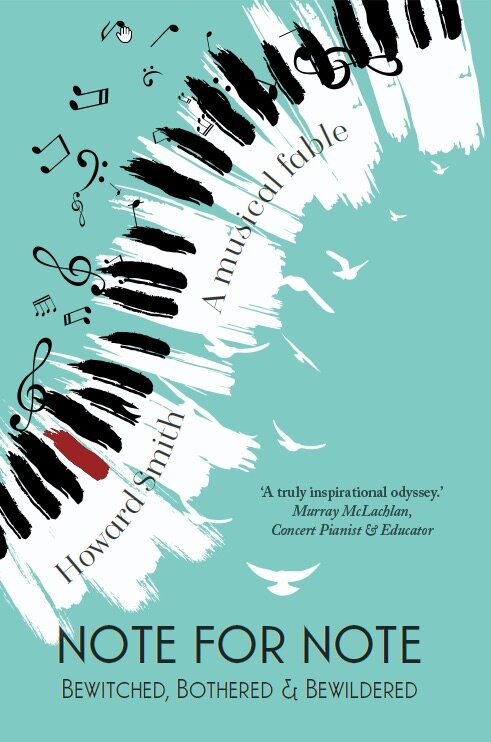

Internationally recognized technologist Howard Smith is one such pianist. In his book, Note for Note: Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered, he chronicles his journey from “adult returner” to pianist and author. He shares his successes and failures. In what is essentially a love song to learning jazz, he explains the intricacies of theory and technique. He speaks of how his piano passion affects his family and friends. Through it all, this big-hearted story reminds us of what a joy and privilege it is to make music.

This guest article is adapted from a chapter of Smith’s book. It’s advice learned from experience, offered as one passionate “adult returner” to another. Thank you, Howard, for allowing me to share it on No Dead Guys.

42 Helpful Hints for Adult Pianists

A guest post by Howard Smith

With time marching on, ambitious amateurs optimize their available practice time to attain the goals they set for themselves. Beyond a certain age, there is a finite window of opportunity to master any complex new skill, and piano is undoubtedly that. Eighty-eight keys. Two hands. Ten fingers. And pedals! More patterns than grains of sand on a beach. While age should be immaterial and attitude is all, our brains do lose plasticity over time. With that in mind, I posed a question to the piano community via social media. It asked:

"In addition to a regular regime of scales, arpeggios, studies and grade pieces, what else would you recommend for accelerated progress?"

The list below is a summary of the suggestions I received.Take from it whatever is practical for you. Personal context is everything: not everyone wants – or can allow – their piano to dominate their life. But for many amateurs it most certainly does. And we love it.

The "advice to ourselves" forms a useful checklist:

Be clear about long-term goals; however, also define a few shorter term objectives. What do we want to achieve this month? Next?

The quality of our practice is more important than its quantity. Aim for what musicians call "deliberate practice": mindful performance.

Maintain regular daily practice; at least five days out of seven. If possible, practice at the same time each day.

Hours-per-day is a debatable issue. Break up longer sessions (more than two hours) into chunks. Not everyone can work as if they are a concert pianist, though some amateurs do!

Combine different styles of practice each day: scales and arpeggios, specific exercises, studies, and of course the music we wish to perform.

Plan our practice time. Divide it between the many kinds of work and study required. Keep to the plan.

Create variety in practice: different keys, modes, contrary motion, legato, staccato, pulse (4, 3, 2), unison, in 3rds, in 6ths, chord inversions, and so on.

Practice slowly, building tempo gradually. Fingering should be 100 percent correct from the get-go. Never ingrain a bad habit; not once.

Easy to forget: hands separately (HS) before hands together (HT).

Build sight-reading skills. Difficult for many adults, but essential.

Use any available time away from the keyboard for additional complementary study. Read and analyze scores.

Listen to as much good music as possible. Listen carefully. Listen intelligently. Watch professional pianists practice and perform.

Interweave a little ad hoc music-making into the everyday. No need to restrict ourselves to formal "sit down" practice. Touch and stroke our keyboard whenever we can.

Learn to play in different styles and genres. If our preference is classical, try jazz, and vice versa. If we prefer modern music, try baroque. Mix it up!

Meet up with other musically inclined people. Join a piano circle. If possible, sign up for a masterclass or two. Consider enrolling at a summer school.

If possible, collaborate with other musicians: join a band, play duets, collaborate on songwriting, etc.

Record our practice and, if possible, our performances. Listen back. Compare ourselves to the recordings made by professional musicians.

Understand the score beyond the notes. Tease out the music’s style, patterns, contours, harmony, texture and structure. Theory is vital.

Look for supplementary advice to complement regular lessons, e.g., YouTube channels, blogs, other teachers.

Feel free to spend time in mindless wandering at the keyboard. Improvise. Have fun!

Always question our progress. Where are we weak or vulnerable? Ask our tutors to diagnose problem areas. Dedicate a lesson or two to this introspection.

Build a more robust technique. And strength in our hands. Yes, scales and arpeggios count. Articulate clearly. Legato and staccato.

Make sensible use of a metronome.Slow down for intense practice.

Short studies (or extracts of longer works) help build skills more quickly

than extended pieces. There is value in practicing tricky bars and phrases,

even if not completed to "performance" standard.

Observe other players; go to concerts, or watch online.

Choose repertoire we love and come back to these works time and again.

Make a list of our conquests. They are our children.

Listen to what our teachers say, and do what they ask. Think like a child.

Soak it up.

Play and improvise against recorded or computer-generated

accompaniments – just for fun.

Try to hear the music in our head, feel its contours before we begin to

play. Add landmarks on the score to help with memorization.

Sing as we practice.Sing the melody line.Sing the inner parts.This will

help to voice our chords correctly and bring out the melody.

"Efficiency of practice" stated as a goal may not be a good metaphor. Enjoy

the challenge of working on intricate ‘impossible’ pieces. Revel in the

journey. Worry less about the future.

Being in a hurry can limit our development. Patience, yes, but keep an eye

on our progress. Is our practice approach working? If not, get advice, change the way we work.

Graded exams are useful milestones and evidence of our success, of which we should be rightly proud, although they are not for everyone. Time can be lost over-perfecting a handful of set pieces for a picky examiner.

Seek out high-quality, challenging repertoire that gradually introduces new demands for the advancement of technique.

Always be on the lookout for new ways to practice. Be creative. Consider getting advice from teachers who specialize in pedagogy.

Never underestimate the benefit of correct finger, hand, arm and body movements. Healthy posture is vital. Eradicate all tension. Try Pilates.

Work with teachers who have ambition for us. Insist they push us forward. Look for what limits us, then hone our effort there.

Always have a sharp pencil and eraser to hand. Scribble all over our scores. Make notes on fingering, harmony, phrases and landmarks.

Invest in our memory. Practice memorization techniques. Learn to perform without sheet music or lead sheets.

From time to time, return to and refresh and enrich our older repertoire; the works we cherish. How have we progressed? Give ourselves a pat on the back.

There are limits to learning the piano. It can rarely be rushed, and absorbing new patterns takes time. Try not to be too hard on ourselves.

Stay healthy. But don’t forget to have a bar of chocolate or mug of coffee to hand; whatever your poison happens to be. But not too close to that precious piano!

From the Postlude to Note For Note: Bewitched, Bothered & Bewildered (Paperback 360 pages, ISBN 978-1999846718, available via Amazon)

Howard Smith (1957-) was born in England and grew up in Kent. An internationally recognized technologist, in 2017 he decided to leave the computer industry he loved to pursue a new life in music. His new book, Note for Note: Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered tells the inspirational story of how he navigated his transition from the bits and bytes of the music industry to the world of melody, harmony, and musical performance. Howard lives in Surrey, England, with his wife.